Marco Mariani panelist at the 2024 Barcelona conference meeting on “Climate change litigation”

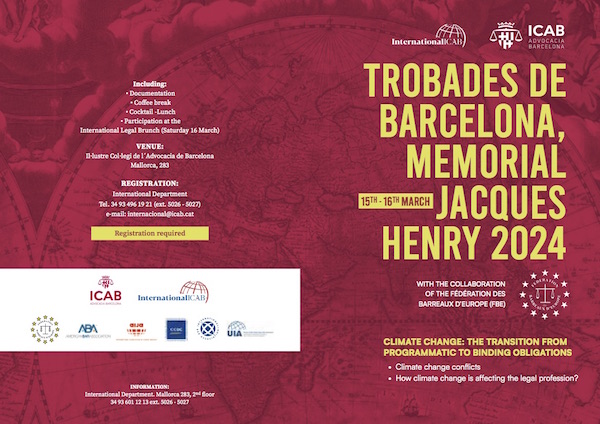

From 14th to 16th March 2024 the Council of the Barcelona Bar Association, in collaboration with the Fédération des Barreaux d´Europe (FBE), organized in Barcelona the conference meeting ”Trobades de Barcelona, Memorial Jacques Henry”, dedicated to “Climate change: the transition from programmatic to binding obligations”.

Ms Rosa Isabel Peña (founding partner at Lex Administrativa Abogatoria and Barcelona Bar council member responsible for the International relations) welcomed the participants and introduced the first working session, focusing on “Climate change conflicts”.

The panel moderator (Ms Noemí Blázquez Alonso, lawyer in the Barcelona office of Uría Menéndez and President of the International relations commission at the Barcelona Bar Association) introduced the topic and addressed some relevant questions to discussants, namely Mr. Marco Mariani (partner at the Catte Mariani Law Firm in Florence, President of the Administrative Law Committee at the UIA-International Association of Lawyers and Lecturer in several Italian universities), Ms. Elisabeth de Nadal (partner at the law firm Cuatrecasas and member of the Barcelona Bar Association), Mr. Philip Henson (partner at the law firm EBL Miller Rosenfalck, President of the Westminster and Holborn Law Society), Ms. Chi Huang (from the law firm Formosa Transnational, and member of the International Affairs Committee, Taipei Bar Association), Mr. Olivier Laude (council member of the Ordre des Avocats à la Cour de Paris, Co-Secretary of the International Committee).

Here below some questions and answers provided by Marco Mariani.

Q: A conflict arising from climate change is the increase in lawsuits against governments and companies accusing them of contributing to climate change or of not taking adequate measures to prevent its impacts. In this regard, are there cases in your jurisdictions where litigation has led to significant changes in government policies? To what extent have the courts recognised and protected the rights of people affected by climate change?

Marco Mariani: A State cannot only combat climate change, having the means to do so, but also has a duty to do so. A duty that is not only moral, but stems from a general obligation to combat climate change (Paris Administrative Court, ‘Affaire du Siècle’ case, judgment of 03 February 2021), a distinctive feature of climate law (Framework Convention on Climate Change, 1992; Kyoto Protocol,1997; Paris Agreement, 2015). It is a complex obligation to reconstruct because it intertwines different fragments of international law, developing on different normative levels in a path that however, has its ultimate goal the fight by States against anthropogenic climate change. The primary source of this obligation is to be found in the Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992), perhaps the most relevant outcome of the United Nations World Conference on Environment and Development in Rio de Janeiro (1992). The Framework Convention, indeed, represents the first attempt to frame legally the climate issue, in the wake of the scientific evidence that was emerging in the 1980s concerning the greenhouse effect, the hole in the ozone layer anthropogenic climate change (the International Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, was established in 1988). In some particular cases of climate litigation, the main intention of the plaintiffs or litigants, in fact, is precisely to affect policy choices that often suffer from shortermistic logic, shun the prospect of the future or (worse) wink at pseudo-scientific denialist theories. Cases must be approached by assuming the reasons of science (normally revolving around the evidence provided by the IPCC reports) and in the possibility of using the rights argument with the ultimate aim of restricting, as much as possible, the discretion of the political-majority decision-makers. The first civil action brought against the Italian State (represented by the Presidency of the Council of Ministers) because of its insufficient political action in the field of combating to climate change in Italy, started in June 2021 and was significantly named “Universal Judgement” by the plantiffs. The legal base of the civil action before di Civil Court of Rome, are articles 2043 and 2051 of the Italian Civil Code (setting the liability of the Italian State for violation of the human right to a stable and safe climate, reconstructed under articles 2 and 32 of the Italian Constitution and art. 6 TEU), due to the lack of commitment made in the field of environmental policy. The claim aims to obtain an order to reduce emissions of greenhouse gas emissions by 92% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. This lawsuit fits perfectly into a massive legal dispute that, having begun to develop, albeit with profoundly different profoundly different, in the USA , has spread throughout the world and, starting with the well-known “Urgenda” case , has also taken hold in Europe. After assessing the possibility of civil remedies against companies that emit greenhouse gases and against the greenhouse gas emitters and against the European Union, one can examine the possibility of obtaining civil law protection against the Italian State. More in details, in the case Giudizio Universal the plaintiffs consider the Italian State the only entity capable of controlling and reducing emissions in its territory, and so the State is liable under Article 2051, as custodian of its own territory. For these reasons, pursuant to Article 2058 of the Italian Civil Code, it is asked the civil court for a ruling that condemns the State to adopt initiatives to abatement of greenhouse gas emissions, necessary to achieve, based on the best science available worldwide, the stabilisation of climate and at the same time to protect human rights for present and future generations, in accordance with the constitutional duty of solidarity and with the international duty of fairness between states. In particular, it would be respectful of the human rights of present and future generations a national framework that pursues the goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 92% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels. There are many legal proceeding issues related to such claims. Just to mention a few: jurisdiction (the civil or administrative one?), limits of the Judiciary Power before the State itself and its branches;3) redressability because they are likely collective rights; effectiveness of climate change litigations; necessary elements of a sufficient set (ness) with the proportional liability.

Q: Business law firms are increasingly adapting to the evolving landscape of climate change laws and regulations. While corporate social responsibility involves companies adopting ethical and sustainable practices in their operations to contribute positively to social and environmental well-being, a notable issue arises. Companies often resort to misleading information and advertising, distorting the portrayal of their activities to falsely convey a more environmentally friendly image. In this regard, in the companies you advise, what corporate social responsibility obligations do they have in relation to the environment and how do companies incorporate sustainable practices into their operations to minimise their environmental impact?

Marco Mariani : It’s worth mentioning the Green policy of an Italian company based in Milan, called EDISON (EDF Group), working in the energy sector and with a turnover of around 4 billion-euro and EBITDA of 1,8 billion-euro. For Edison, committed to leading the energy transition for its customers, suppliers, communities and territories in which it operates, these challenges implied a renewed commitment. Over the last fifteen years, Edison has significantly and progressively reduced its direct CO2 emissions by more than two-thirds, from almost 25 Mt in 2006 to the current 6.9 Mt. Edison has been assessing the short- and medium-term impact of climate change for several years as part of its risk management model (ERM process), evaluating physical and transition risks to 2030. Starting in 2021, Edison supplemented the ERM assessments by developing a plan that assesses the resilience to climate change to 2050. The Company conducted an assessment to evaluate long-term chronic and acute physical risks and to draw up the most appropriate mitigation actions. The scope of the analysis involved all of the main generation plants, both thermoelectric and renewable, and the main Edison Next sites. The assessment was conducted using scientifically recognised scenarios consistent with data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and showed a low risk on almost all infrastructure for short/ medium-term risks (by 2030). The study also made it possible to outline the mitigation actions associated with the medium/long-term risks (2030-2050) that will be assessed in an implementation plan that is currently being drawn up. The company’s day-to-day and responsible action in terms of natural resource management continues, also linked to certifications and environmental management systems. Allow me to mention the Edison daily commitment in complying with “green public procurement” principles, purchasing products and services that cause minimal adverse environmental impact. Furthermore, communication, awareness-raising and dissemination actions are crucial because climate change is fought through the commitment of institutions, businesses and civil Society. In keeping with this spirit, throughout the year the Company promoted days for in-depth reflection relying on the collective intelligence game “Climate Fresk”, in order to raise the awareness of all employees on this topic. Starting in 2021, Edison invited its people to think seriously about the issue of climate change while still having fun through “Climate Fresk”, a collective intelligence game for understanding its trends and reflecting on the best possible actions to counter it. Participants meeting around a table (or even digitally) use 42 cards, representing the variables of the phenomenon, according to the links identified in the IPCC reports on which the game is based. The construction of the “climate fresk” is followed by dialogue between participants, who can exchange reactions to the evidence of connections and effects and discuss individual or collective solutions to combat climate change. The game, disseminated internally thanks to a community of 30 facilitators, involved 170 colleagues from different locations due to the organisation of company Open Days and events dedicated to specific locations and company divisions. In conclusion, Edison is a solid company that is seriously managing climate issues, but, frankly speaking, not every company in Italy is able to comply with that standard.

On 26th November 2021, the first precautionary ordinance of an Italian Court on greenwashing was issued, an act that is also among the first in Europe: after the measures of the Italian Advertising Self-Discipline Jury and the Italian Antitrust Authority. In its advertising campaigns the defendand company used statements such as ‘the first sustainable and recyclable microfibre’, ‘100% recyclable’, ‘environmentally friendly’, ‘natural choice’ and ‘ecological microfibre’. The Court of Gorizia acknowledged the potential danger for the Palintiff (a company competing in the same field) by stating in its judgement precisely the principle set out above, such as: “the sensitivity towards environmental problems is very high today and the ecological virtues extolled by a company or a product can influence the consumer’s purchasing choices”. The Court itself stated that a series of environmental claims used for the product “Dinamica” (such as, in particular, “environmentally friendly” and “natural choice”) “are certainly very generic and certainly create in the consumer a green image of the company without, however, actually giving an account of what are the company policies that allow a greater respect for the environment and effectively reduce the impact that the production and marketing of a fabric derived from oil may have in a positive sense on the environment and its respect”. That decision was reversed in the second ground. Furthermore, in November 2021, the Lazio Regional Administrative Court rejected the appeal filed by the Italian company ENI against the measure taken in 2019 by the Italian Antitrust Authority which it had ascertained the unfairness of the company’s advertising campaign, focused on the ecological value of Eni Diesel+ fuel. Furthermore, I could mention decisions from the Italian self regulatory institute on marketing communication (IAP). The IAP is not an authority, nor is a judicial body, but it is an association of companies that brings together most of the companies operating in the advertising sector. The injunctions of this institute block an advertising campaign and order the publication of the ruling through the media outlets indicated by the Jury. In recent years, the IAP has produced many injunctions against companies responsible for untruthful green messages. For example, in October 2021, it went against the Findus spring peas ad. “The commercial read ‘spring peas are tender, sweet, small, sustainable because they respect the environment and you too’. You cannot say something like that because in the vagueness of the sentence it is clear that the advertised product mentions “sustainability” on the one hand and “respect for the environment on the other” without there being a scientific basis substrate that makes it clear what it is talking about, what stage of the production cycle and in what sense it is talking about sustainability.

Q: Finally, in Spain, more and more law firms are becoming aware of the multidisciplinary nature of the legal issues related to climate change, as addressing these issues requires not only legal knowledge of environmental law, but also knowledge of urban planning, international law, criminal law due to the existence of environmental crimes, and also tort law, as it often requires non-contractual liability. It could even affect issues of project and operational financing and, as mentioned above, corporate social responsibility. Do you consider it appropriate, or do you already have a department or coordination group in your offices, whose purpose is the cross-cutting advocacy on these issues?

Marco Mariani: according to my personal opinion, litigation on climate change will tend to focus on four potential macro-areas: 1) litigation on the non-contractual liability of companies, accused of having contributed by their conduct to climate change; 2) actions against states, which will be accused of failing to take appropriate measures to reduce pollution levels; 3) lawsuits brought by insurance companies against companies; 4) social responsibility actions, brought by shareholders who do not agree with the choices made by company directors’.

These are all complex disputes, because they require us to ascertain conduct that originated in the past, the effects of which are exploding now. Moreover, it is very difficult to identify responsibilities and apportion them when several companies are involved, as is often the case in US class actions.

The litigation originally focused against the States, but now ‘the focus is increasingly shifting to companies. Initially, companies that produce hydrocarbons were involved, because it is easier to relate their activity to the increase in greenhouse gases. But now, the focus is also shifting to other more “unsuspected” business sectors, such as IT: technology companies use large amounts of energy and are questioning the risk of being subject to litigation for their impact on the climate.

A topic recently explored in depth by some big legal firms is the possibility to establish a link between a certain activity carried out by a company and damage to the individual. This broadens the possibility of companies being sued. Lawyers, therefore, on the one hand must equip themselves to handle climate change litigation, on the other hand, there are the insurance spin-offs: lawyers must support companies in revising their products to cover risks arising from exceptional climatic events; then there is already the risk of directors suffering social responsibility actions, which are also on the rise due to legislative changes that impose stricter obligations in corporate governance to protect the environment. More and more often, stakeholders are suing the board held responsible for non-compliance with the rules, which leads to sanctions, even serious ones such as the seizure of plants or factories that can result in the blocking of production activities.

I have a small law firm and to manage these issues I closed agreements with other professionals skilled in environmental related issues. Furthermore I’m quite involved in several universities courses concerning climate change at the Camerino University (2021) Venice University (2022), Milan Statale University and Sassari University (2023 and 2024), such as Planning Law, Environmental Law, Forestry Law.

In conclusion, addressing climate change conflicts requires a comprehensive understanding of different branches of law. It emphasises the need for a holistic approach, recognising that these issues are no longer marginal, but continue to escalate in both quantity and quality. As such, addressing these challenges requires an interdisciplinary and forward-looking perspective within legal practice. Legal professionals are, indeed, relevant stakeholders and few months ago the International Association of Lawyers (UIA) issued a Resolution on Sustainability and the role of the legal profession which emphasises the importance for the legal profession in promoting sustainability, human rights, and the Rule of Law, with a view of encouraging a sustainability-minded legal profession. In particular, the UIA calls upon all Bar Associations, Law Societies, and legal educational institutions to promote the legal profession’s consideration of sustainability as strictly related to the promotion and protection of human rights and the effective enjoyment of human rights and fundamental freedoms and offer services to clients and members that wish to enhance the sustainability of their policies and practices; to facilitate dialogues to create solutions to the crises posed by climate change, loss of biodiversity, water management, and the need for a circular economy. Furthermore, the UIA resolves to view its internal practices through the lens of sustainability and, where practicable, institute policies that reflect that view; to raise awareness of the SDGs among its members and actively support the United Nations and other institutions in their efforts to achieve the SDG agenda; to develop best practices for lawyers and law firms that include the Ten Principles of the UN Global Compact, the SDGs, and ESG factors.

PP/com.unica, 16 marzo 2024